Recession, paper, breakdown, culture.

"But when I say starvation, destruction, migration, disease and war, I mean in your own life. With the power down, soon you wouldn’t have water coming out of your tap. You will depend on your neighbours for food and some warmth. You will become malnourished. You won’t know whether to stay or go. You will fear being violently killed before starving to death."

Jem Bendell wrote those words last year in his startling paper, "Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy". I've spent the last few days trying to digest it, along with a number of other things swirling around in my head.

It feels like we are reaching a heightened state of fear and panic about the future. Bendell makes the point at various places in his paper, that the future is uncertain. Nevertheless, there are key indicators to suggest that we will soon be entering into a series of feedback loops which will uncontrollably change both the climate, and our civilisations: he talks about methane released from the seabed underneath the arctic. He talks about the fires in that region - which have been in the news (again) this month. For him, these are not outliers, these are the forms of the new age we are entering into. And it will not end well.

This new age takes two flavours: the world will change and nothing will follow. Or, the world will change, and something new will emerge. This is where people's natural outlook plays its biggest part I think. Do you think the world will end, or do you hope we will endure?

Taking a step back, almost physically from my laptop where I read the paper, I tried to make sense of this pivotal moment. Here we are, on the brink. If you listen to some people, it's the point of no return. For some, we still have time to limit the worst of it. For others, like Bendell, we are actually past that moment, and now it's about creating 'deep adaptations' to our civilisation in order to survive. For others, this is not even a problem: the changes in temperature and climate mean we can holiday in the UK rather than Spain. For myself however, I tried to contextualise this apocalyptic vision inside my own lived experiences.

As a result of my own experience, with the things I was absorbed to, I have to consciously shut out the cultural touchpoints surrounding apocalyptic visions, which have entered my imagination over the last 30 years or so.

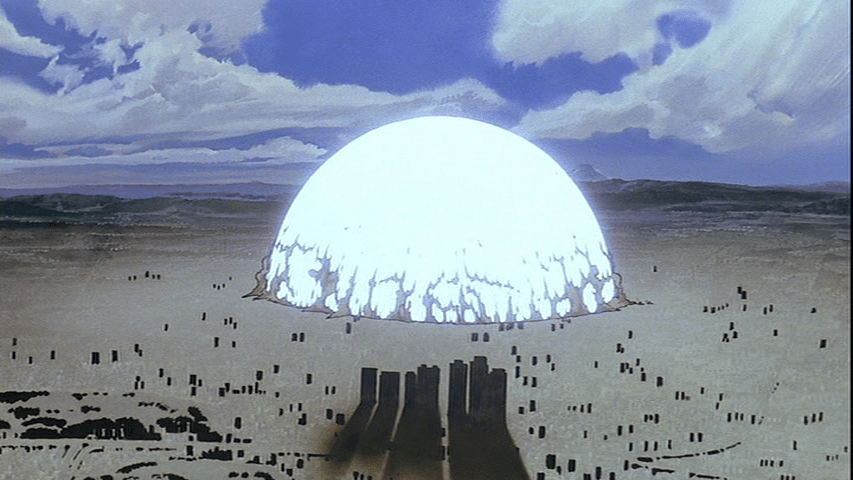

I watched Akira when I was about 9, its beautiful, dense, point-lit Neo-Tokyo rising out of the rubble of nuclear war was both beguiling and terrifying. I watched Terminator 2 far too young, and had nightmares about being trapped in playgrounds when the nuclear bombs fell. These were hangovers of the nuclear terror, the defining horror of the Cold War which I was born into. As a teenager, I loved George Romero's Dawn of the Dead, with its anti-consumerist commentary, but the zombification of culture - from smartphone addiction, to declining voter turnout - leaves a bitter taste in the mouth. But now, now we have this even bigger mysterious, emotionless terror to face: the planet itself.

And yet, as I thought about it, there was twinges and memories of the end of the world, that had happened to me as an adult. I remembered: we've been here before. I didn't have to imagine what the death of the world order looked like. I'd already experienced it. In an interesting twist of timing, I both experienced the collapse of one world order, while being exposed to the most potent excesses of it.

In 2008, I was working as a freelance designer for a design studio in London. It was very early in my career (I'd graduated a year earlier) and was brought on to help design art catalogues for the Gagosian Gallery in New York. The project itself was incredible: I got to work at one of my favourite studios, alongside one of the directors whose reputation was unparalleled. I got to learn from the master. I was able to see first hand his decision-making process for picking paper stocks, his intuition about layouts, printing process, typographic choice. It was like drinking fresh water from a mountain stream. I was in heaven.

We'd gotten one book under our belt (a stoic catalogue for sculptor Richard Serra) and we were working on the second, with a third on the way. This second was for Richard Prince, the American artist. He's most famous for his Marlboro Men series, pushing the boundaries of ownership, copyright and semiotics. His paintings, taken from advertising are in a way, the natural successor to Warhol and their pop consumer dirge.

This latest body of work, born out of the excesses of the New York art scene in the late 2000s, was called Canal Zone. The paintings - collages of donkey's, pin-up girls, Rastafarian men with crudely pasted guitars and elliptical shapes - were grotesque, horrific, exploitative pieces. I took great pleasure in creating the crops for detail pages, focusing in on particularly contrasting textures and badly placed materials that really exposed the materiality of the pieces rather than the pornography of the images. The artist reportedly like them.

The pieces - as is usual for catalogues - had an essay that accompanied them, inside the book. It was written by James Frey. Frey is famous for writing his own autobiography, but making it all up. He has a directness which is exposing. We selected a very jolly looking typeface that would not be out of place at a Chicken Cottage menu. It was the best way to mask the terror.

I was working on that book, that essay, some day in September 2008. I was watching the RBS stock go into freewill, with detached bemusement. It was my bank - I grew up in Edinburgh and opened my first bank account at their head office in St. Andrew's Square - but this felt strange. It was like watching capitalism destroy itself.

As I recall (though its probably different in reality) it began with Lehman Brothers, and then it hit others, and then Northern Rock, and then RBS and others. It was a chain reaction. Like Hemingway said about going bankrupt, it happened "gradually, then suddenly."

I was watching - as many of us were - what it was like to watch an economy come close to collapse. This was essentially the collapse of the neoliberal world order. Everything had finally caught up with it, the feedback loops had become unsustainable, the nature of man was being horribly, brutally corrected by the science of economics.

But the interesting thing was, I was working on a catalogue that was viscerally describing what came after.

Back in 2019, Wwhen I read Bendell's paper on the imminent collapse of our civilisation as a result of the runaway climate breakdown that is about to happen, I immediately remembered the essay that James Frey wrote, to accompany this horrific, broken down series of paintings of mankind run amok.

I digged around my files and re-found it, and I've placed it in full below. It still haunts me, as a rapid progression of one world order, dragged into a new one. It's over the top - like the paintings - and features caricatures, and dramatic exaggeration (it is a piece of fiction after all). But still, the story, the artwork and the catalogue all signal the death throes of one civilisation - one born out of Cold War fear and neo-liberal financial excess - and replaces with another. It was titled, 'Ding Dong The Witch Is Dead'

–––

You are forty-six years old.

You are married and you have two children, teenage girls, thirteen and fifteen, they are supple, budding, on the edge of womanhood.

You work in finance. You are a partner in your company. You have forty million dollars in the bank, a Fifth Avenue co-op, a house on the pond in Sagaponack. You belong to a club in the city, and a club at the beach. You have a driver, a Mercedes and a Range Rover out East, your daughters both have horses.

You never fly commercial.

You never buy off the rack.

You never cook or clean you have people who do that for you.

Every year at Christmas you and your family go St. Barts. You stay at the Eden Rock in a suite you eat at La Plage, at des Pêcheurs, On the Rocks, Do Brasil. Your friends are all there some have yachts 200 foot pleasuredomes with millions of dollars of art on their walls, some rent houses, some are at your hotel, others nearby. You spend ten days eating and drinking and fucking sometimes your spouse, sometimes not. Your daughters lie on the beach and gossip with other girls and flirt with boys and disappear at night.

You’re going early this year, hey why not, the weather has been shitty in New York and political turmoil Russians Arabs Chinese fuck ’em all have been making business difficult.

Your driver picks you up everyone’s excited woohoo woohoo he takes you to Teterboro. The Gulfstream is waiting you only own a share of it someday the whole fucking thing will be yours. You get on. Your girls are texting their friends they have dvd’s and computers. You and your spouse each have a drink and go to sleep. You fly it’s fast and easy and extremely comfortable. You land there are people waiting for you they gather up your luggage and take you to the hotel. You check in everything is beautiful, perfect, expensive, somehow it evens smells of taste and luxury, it’s just the way you like it, just the way, another Christmas on St. Barts, lovely.

You have dinner drink too much the girls leave you go to bed you and your spouse both scream while you fuck even sex is better here.

You go to sleep. On sheets that cost more than most people on the island make in a year. Who cares. Fuck them. Let them sleep in dirt. As long as the food is warm and the drinks are cold and everything stays perfect. You go to sleep.

Peacefully.

Sleep.

–

You are shaken awake. Your daughters are in your room they know they are not supposed to come into your room, in New York it’s fine but not here, not on vacation, not when you might be doing something you don’t want them to see, they are thirteen and fifteen.

They looked shocked, terrified, hysterical. You immediately think they’ve been raped (not yet, my friend, not yet). You come out of sleep quickly ask them what’s wrong they’re both shaking their entire bodies somehow shaking one of them says it’s over, everything’s gone, the other immediately starts sobbing, everything’s gone.

You get out of bed. You tell your girls your beautiful young, supple, budding, on the edge of womanhood girls to calm down they don’t, they can’t, they both fall apart, neither can speak. You hug them your spouse wakes wonders what’s wrong you raise your eyebrows you still don’t know.

You still don’t know.

You still don’t know.

Your spouse gets out of the bed your older daughter calms down enough to say there was a war.

Was?

Everything’s gone.

Everything’s gone.

–

Not everything, but pretty fucking close. Every major city in North America. Every major city in Europe and Russia. The entire Middle East every city town village hamlet every mud fucking hut. Pakistan and India bye-bye. China bye-bye, though there is so much there that some may be left, no one knows, no one knows. There’s some desert in Australia, parts of the Reef. South Africa burned the rest soon to follow. Japan hit again it is no more. South America incinerated. Iran fired first. Israel responded. Then Russia. Then us. Then it didn’t matter who fired or when or where all of the buttons were pushed. Kaboom. Kaboom. Kaboom. Over and over and over and over, again and again and again. Kaboom. Not everything, but pretty fucking close.

–

First day you’re shocked.

Second day you’re scared.

Third day you’re confused.

Fourth day you’re panicked.

Fifth day you fall apart.

Sixth day there’s a riot.

Seventh day doom.

–

Your money is worthless. Your job and title and degrees mean shit. Your apartment and house are gone. Your parents are dead. Your friends are all dead. Everyone you know, except for your spouse and children, are all fucking dead. The restaurants, galleries, shops, and boutiques that meant so much to you, that were so much a part of your life, that were so fucking important, they’re ash. The school you went to, ha ha ha ha ha. The place where you were married, no longer. Everything that was, is no longer. That includes hope and love and the future. No longer. Ha ha ha ha ha .

–

The hotels become encampments. Water, food, and bullets become currency. Women become slaves. Some cook, some clean, some carry children, some take care of children, some care for the sick and the wounded, some care for prisoners. Some of the women become objects of pleasure and they are defiled, defiled every day, defiled in every way you can imagine. The weak become the strong. The fist rules the mind. Words you come to live with and know include force, brutality, violence. Fear loses its meaning because you are absolutely fucking terrified every moment of every day. You are not strong. Your hand is limp. You live in the dirt. You wear rags. You eat the leaves of trees at night when you’re done working and on good days, the best days, you get a piece of discarded fruit, or a well-chewed bone. When the sun sets, and the fallout has made the sunset beautiful beyond your imagination, you curse it, you curse it, you curse that fucking sun.

–

Your daughters are gone, they were taken, dragged away while you were lying beaten and bloodied too damaged to scream, they went into the hills, they remain in the hills, you don’t know where it’s an endless green mass, they were young, beautiful, supple, budding, on the edge of womanhood, and they are gone.

Gone.

Gone.

–––

Is this our fate?

The economist Mark Blyth wrote in 2016, "the era of neoliberalism is over. The era of neo-nationalism has just begun.".

I've spent a large majority of my adult life transitioning from the old neoliberal world order in which I was born into. That world is gone. The security and tradition of my parent's generation is essentially wiped out. The expectations of my own generation have been snuffed out as a result of the Great Recession. The world, in many ways, has already ended.

The rise of Neo-nationalism is one indication of the collapse we may already be experiencing. Which provokes in me, the most unusual feeling: relief.

It's already started. You don't need to hold your breath and wait for the drop. So that means we don't need to be afraid of what happens next, it's here, so what are we going to do about it?